Melt Club in Conversation

On 1 December 2023, the London-based art collective Melt Club opened their first international solo exhibition at the Museu Joaquim Correia in Marinha Grande, Portugal.

Titled Desenrascanço, the exhibition presented the culmination of approximately a year of collaborative practice, seeking to respond holistically to the museum and its context in the small industrial city of Marinha Grande. Alongside its subject, the show represented an extended and at times challenging process of trial-and-error as the group sought to synthesise a working methodology around understanding what it means to work truly collaboratively.

In February 2024, Melt Club sat down to reflect and discuss this process. The following is an edited transcript of that conversation, presented alongside documentation of the show. It offers a candid insight into the life-cycle of ideas – from genesis to development to execution – and contemplates the value of this work to practitioners and communities alike.

In the interest of clarity, the names of the conversation’s participants have been abbreviated as such:

Aline Bittar Künzel (ABK)

Alex Blackbourn (AB)

Christina Da’Prato-Shepard (CDPS)

Tooey Jones (TJ)

Sebastian Elborn (SE)

Maggie Pavlova (MP)

Katie Saunders (KS)

Maite Pereda, who contributed to the show by sending work from her home in Mexico City, was not able to attend the conversation.

Beginning

By the time of the opening, we'd known that we’d be putting together a show at the Museu Joaquim Correia for almost a year. From early on it was clear that both we as a group and the museum had something to gain from this opportunity; here was this low-budget, small-town museum, ambitiously trying to bring new things and different ideas into its town, and we were this early-career group of artists just starting to figure out how we fit into everything. Whilst we knew it would be a challenging task for us, we were also a gamble for them, and so we decided that it was worth doing and we submitted a proposal.

The proposal we put together was actually based on a conversation I’d had with Alex a while ago, before we even knew about this project. It is part of my practice to take elements from different types of imagery and blend them together. In that conversation we spoke about what it would mean to do that with everyone else's work, appropriating their imagery and using bits of other artists’ practices to make a collage. When I'm making work independently, I typically begin by selecting a collection of imagery, changing the colours and the composition over time until it makes sense to me. The individual pieces almost don't matter as much, so it was interesting to think about someone else sourcing that imagery. That image of a way of working was in the back of my mind as this project started.

Of course, as we moved from the way I work individually to collecting imagery as a group, I couldn't really predict how it was going to come together, but it was interesting for us to define that process. Once we took some time and figured it out as a group we got there in a different way but, yeah, I think that's how collaging started for us, in that original proposal.

And then nothing happened for months, and we all mostly forgot about it until suddenly we had dates for an exhibition.

ABK:

AB:

Yeah, I remember at that point we really had to work to reignite the flame for the show because the application had basically been shelved for a few months and there was this feeling between the two of us that we really didn't know what this meant for everyone. There was no momentum whatsoever and we wanted to create a structure that allowed for everyone to be completely non-committal about it.

Soon after that I went to Portugal and took photos of the space, and I think that’s when it started taking shape.

ABK:

In June 2023, Aline and I made a large painting together thinking about the Lisbon earthquake and tsunami of 1755. From my perspective, that’s where the first seeds of what specifically became Desenrascanço were planted. We weren't at all sure what to do, but we'd done a little bit of research and I was obviously very struck by this historical link between the earthquake in Lisbon and Marinha Grande as a glass making town; where in the wake of the destruction caused by the earthquake and the subsequent tsunami and fire, Marinha Grande's industry was pushed forward by the Marquis of Pombal in an effort to rebuild Lisbon. This led to us thinking about the push and pull between ecological circumstances and human decision-making that really defines Marinha Grande in a lot of ways, in particular in relation to the Pinhal de Leiria – I guess there's some Desenrascanço in that already.

AB:

In the 13th Century, the city of Leiria relied on farmlands surrounding the city that were now finding themselves at risk of sand erosion from the nearby coast. To protect their main source of food, King Afonso III and subsequently his son, Denis, planted a forest of pine trees, the Pinhal de Leiria, to form a natural barrier between the city and the coarse winds from the west. The solution was successful, the farmlands were saved and Leiria would continue to thrive.

The Pinhal de Leiria, the “available means” of the 13th Century, would occupy a similar role five-hundred years later with Lisbon’s devastation by the great earthquake of 1755. Again the forest offered a solution, this time as a source of fuel for the Royal Glassworks that would play an essential role in rebuilding the city, in turn building a community around its industry that would grow into a town of its own right: Marinha Grande.

Today, little remains of the once-eleven thousand acre forest due to the decimating Portuguese wildfires of 2017.

As a way of articulating this research, we experimented with painting directly onto the same fabric at the same time. We certainly did not expect the work to be very good or that it would necessarily exist within the final show, but we hoped it would be at least generative.

At this point we were drawn to working with fabric, specifically because it was most convenient to transport. Still it was quite tricky to understand what we were doing with that and I was very unsure about how to start, especially after a few very lost meetings as a group.

At the same time, our entire idea for Melt Club – us working collaboratively and “melting” our practices together – was very much this idea that we had never really put to the test. What did it mean for our work to really “melt” together? We had this understanding from the beginning that the show wouldn't just be each of us bringing in a piece of work and putting it on the wall, but we also never really did anything to break those boundaries, so it was hard to figure out how to start. Now it feels very obvious and natural that it ended up the way it did, but it wasn't that clear at the time. I wasn't there the first time that you all got together to paint as a larger group, how was that?

ABK:

AB:

We tried! But there certainly was this feeling of “what are we doing?” The realisation there was that you and I, Aline, had found that painting together worked for us because we have a shared background in painting and a similar approach to image making, but that we wouldn’t be building a show in this way because it just didn’t suit most people's practices.

Yeah, that day was definitely when I realised that my art practice is actually quite a solitary one. I was quite stressed out with it being a very painting-focused setup, and I just wasn’t used to that. We were unsure of exactly how the “melting” was going to happen, and there was a point where we thought that it would just happen through making our work in the same physical space, but ultimately this wasn’t going to happen. It became more that we would make individually and then bring our work together to assemble collaboratively.

CDPS:

AB:

It’s surprising to me that of all the things that were made that day, actually quite a few pieces made it into the show. I suppose in hindsight it wasn’t a complete failure.

Cause and Effect

After doing some thinking, and with Alex having done some research about the Pinhal de Leiria and its entwined history with Marinha Grande, we had a conversation with Christina and Maggie in Hampstead that felt quite significant. That was the point where the ideas started to exist in a more real way after talking through our early themes, and where the concept of Desenrascanço started - even though we didn't have the word yet. We also identified the idea of nature as something that forces humans to respond as an important early theme.

ABK:

This led to talking about the specific circumstances of ecological chance and chains of cause-and-effect coming together to create this town in the present day with the forest as this real signifier of that tumultuous history. For me at least, that was a very amazing thing to think about.

AB:

That conversation was when things fell into place for me. Before that, I had been struggling to find a perspective I could bring to something I had zero knowledge about, but then Aline mentioned Penelope from Greek mythology and her story of weaving and then unweaving. I had already been working in a similar process with crochet, so I continued to explore the act of making and unmaking, but through weaving as Penelope did. We also spoke about textiles as a form of documentation, and these two themes led me to want to document my own weaving and unweaving process.

To achieve this, I applied dye over each version of the weave, becoming interested in how this repeated process affected the way that the fabric absorbed the colour, which aligned with this idea of cause and effect we had previously spoken about. I was also experimenting with natural dyes, which added another element of chance to the process as I never really knew exactly how the colours would turn out. Each of these aspects culminated to record not just the time of the weaving process, but also the act of starting over and trying again.

CDPS:

In Homer’s The Odyssey, Penelope waits for her husband, Odysseus, to return home. In his twenty year absence, Penelope resists the advances of over a hundred suitors, refusing to abandon her loyalty to her husband and marry another man. During this time, she promises to choose a suitor once she finishes weaving a burial shroud for Odysseus’ father – a task she knows shall never be complete. In the day she weaves and at night she unravels her work, repeating the process the next day, and the next, and the next... for three years until her plan is exposed.

Running With Scissors

Once we had a slightly clearer idea of our process and what our medium would be, we discussed having a base for the work that would tie each of the individual pieces together. When we later got together and spoke about what that base might actually look like, I have this clear memory of Alex taking a sheet of paper and drawing these lines that were recognisable as trees.

ABK:

I wasn't there for a lot of the first meetings when you were really figuring it out, but I think we answered a lot of questions on that day, and more specifically that we would cut these tree shapes and sew them together.

TJ:

We also calculated how large it would be, how much fabric we’d have to buy and how many pieces we were meant to cut. We really underestimated how long every step of it would take, but we got there in the end. Then there was the meeting at Katie and Tooey’s place, where we did the cutting…

ABK:

Oh my god, that was when it was like we’d joined a cult; there were so many crazy moments that evening with us ending up all wrapped up in the fabric.

KS:

[Everyone laughs]

I genuinely think there was something in that fabric that made us all go a little bit mad.

CDPS:

ABK:

Yeah… it was a good thing.

It can be such a joyful act to make in a way that is so unfamiliar – and I know some of us work with fabric, but none of us work like that. It was very freeing and it was a nice moment to just run with it. Literally. With scissors across the room.

AB:

It was just the size of it – I think that day we realised how huge it was. We knew it was going to be big, but we felt like we’d be able to move it between our flats; after that day it became clear that it wasn't going to work like that.

ABK:

What was funny as well was the way that we were working collaboratively. Someone can very easily cut a piece of fabric by themselves, but we chose to do it as a big group with everyone holding the fabric and then each of us taking turns with the scissors. We really put making it together into every literal thing.

CDPS:

We made it a ritual. It was so ritualistic. From there our process quickly took the shape of regular meetings, taking the bits and pieces of what we had from those weird little workshops, cutting them up, trying to turn them into something.

AB:

Desenrascanço

Pronunciation: “De-zen-has-can-so”

The act of disentangling yourself from a difficult situation using available means

To be fair, when we were trying to come up with a title, I found the word ‘Desenrascanço’ mostly because Alex was trying to make up words, like put words together and make something up that no one would know what it meant apart from Alex. I thought maybe we should find a word that actually means something!

So – like that scene in Twilight – I was literally googling: ‘Portuguese words with unique meanings’, and I think I came across a video that used it. And, yeah, what can I say…, I like big words and I cannot lie. It's because I'm pretentious and I really like big, complicated words that mean fun things. The video was this woman talking about fishing in Portugal, and she used Desenrascanço to describe the fishermen making do with what they had and building these platforms in the middle of the sea in order to fish, continuing their trade using any available means in order to support their families.

And, obviously in a much less serious way, that was kind of what we were doing. We were grasping at straws, trying to put together a show that would represent us as artists as well as it possibly could, but would also be easy to travel with and put up in like two days.

Yeah, I didn’t exactly know why, but it felt correct. It also felt important that it was a Portuguese word. It made it more accessible. We were bringing a show to a place where Portuguese would be the main language; the main entry point had to be a word that people would actually be able to read and understand.

At the same time, it really catches people. It communicates that we weren’t trying to tell anyone their own history or culture, but that we were trying to experience it ourselves, respectfully, and invite them into that journey.

MP:

I love it, it's just a very simple way of enacting the intention of this work to not just be something that we're doing as like a passion or ego project, but rather that we want this exhibition to be for the people who will be experiencing it, not about them.

AB:

The title definitely had this effect of bringing people in and making them curious… Catia, the museum coordinator, said a few times that she was excited about the title and she even described her experience of working in the museum as this continuous Desenrascanço. She told me:, ‘Oh yeah, that's the Portuguese way of life – that's how we do it here.’ While we were there, people were asking about it all the time, so I think it definitely made them curious and sort of wonder “why are these foreigners coming here and using this word.”

ABK:

That’s really good to hear! I know in the beginning, when we first were talking about using the word, we sent it to your mum to check if it was an actual word or not, and she wasn't quite sure. Was it widely recognised?

MP:

Yes, that was because we don't use that word in Brazil, it's a Portuguese-specific word, so it just sounded very strange to us. When you first mentioned it I was unsure because I had never heard it before. I wondered if it was some really specific word that is only used in certain situations. But when I asked Catia about it, she said: ‘Oh yeah of course, we use that all the time.’

ABK:

AB:

I do think that with that name, with all of this sprawling between us, trying to work out what the show was, what we were making, what the point of it, trying to work out what it means, does it need to have a point… That name became this real binding point that exists on all levels of what we're looking at, what we're doing and what we're going to make.

I think it took the pressure off a little bit too; whenever something wasn't going exactly the way that I hoped I would be relieved because that's the spirit of the show.

CDPS:

Before that we were trying to find some sort of strong statement or purpose to what we were doing and it was really difficult; I guess that became the statement.

ABK:

Familiarity

I made my paintings once everything was coming together, once I knew the plan for the piece. Before that I had been making small bits of work with clay, but after looking at Josefa de Óbidos’ paintings for quite a while and imagining how my work might fit in with everything else, I turned to painting. Even though I had tried to paint more gesturally, the paint looked so thick and opaque when placed next to the other pieces which seemed to dissolve into each other; they kind of stood apart.

KS:

It was quite formal in comparison to a lot of other work, which meant that there was sort of a reckoning that had to happen there, but I do think that was an interesting process.

AB:

It really was. When we brought in our pieces to work on the large collage, I honestly really loved cutting up my paintings and working together to make ways of obscuring them, so that they would fit with everything else. They got there in the end.

KS:

I know you went to your own family archive as a source to use as reference for your paintings as you’d visited the area as a child; how would you describe that experience of working with these images and having this strange, quasi-familiarity with the space?

AB:

This photograph that I found, it wasn't a particularly great photo, but I hadn't ever seen it before, and I liked it because it was of my nan. It is strange looking back at photos of her; she passed away when I was quite young, but we were really close as she looked after me when I was little. It was a nice discovery, finding this picture.

KS:

In the photograph, she has this little lamb under her arm which was my sister's toy. My sister, Emma, who is the little toddler, has this glow behind her because… I don't know… It’s just a bad photo and it was obviously overexposed. She's walking, carrying her stick through this forest which was actually the Pinhal de Leiria, and the whole thing just really captured me.

To paint the forest, I combined the image with a similar pine forest that I'd seen in Croatia, from which I had better photographs of the trees, sort of imposing the two together. I wanted it to be a wash, a suggestion, like a faded memory. I tried to keep the marks loose by using a fabric medium.

I think there’s something very interesting about being conscious of the fact that you don't really know the space, but trying to render an approximation of what that could be.

AB:

When we were in the area to install the show, we drove through places that I've seen before, the landscape and all of the pine trees… It's funny going back to a place that you went to when you were much younger, you remember things differently. You think back to the associations you had then and you feel like a new person.

KS:

Traces

I was very struck by the fact that the show was about a place that I've never been to. I had never even been to Portugal, so I had no reference for anything really, and I remember looking things up online, trying to get a sense of the place, quickly coming to the conclusion: this is just stupid and this is not going to work.

This brought me to this old idea I’d had, very much thinking about mapping and how to map something that you can’t experience. That's where the carbon paper approach came from, using the postal system to source mark-making from a place and process that I was so removed from and could never experience myself, like, I can't ever be a letter going through a machine.

TJ:

I think so much of mark-making is about the human touch on it, and I just really liked the fact that by creating marks through sending letters in the post, the result was completely out of my control – much like a lot of this project, to be honest, because we're working so collaboratively. It gave me a lot of comfort just to know that I can't decide how this is going to come out. So in that sense,I felt that this concept fit really well with this project.

In the end this worked in many ways for the work it produced, yes, but also how it led to me taking other approaches. The pieces I contributed that ended up being put into the tapestry were not exclusively from my initial idea to send fabric attached to carbon paper by post; instead, much of it came from older experiments I’d made with carbon paper in the past, and that allowed me to take all of the ideas that we'd worked with – layering, assembling, appropriating – and then start to use bits of other people's work as part of my own process. The main thing that I got from this is that it was evolving up until the end.

Something feels very desenrascanço about that as well, when you talk about there being this whole project feeling out of your control – especially coming in at a later stage – and if the “available means” are out of your control, there’s something about fully leaning into that, and using your lack of control as the core mode by which you make your work, that seems to speak directly to that. So what happened to the pieces that you sent to Portugal?

AB:

ABK:

They arrived on time, and we did add some of them to the large collage!

TJ:

You did! I wasn’t sure if it had actually made it onto the installation. [laughs] Okay, that's good!

Yeah, I don’t think we ever directly told you about it, but we did! They were delivered to my parents' apartment in Caldas de Rainha, and I opened them when I arrived. There were a few different envelopes, and some of the attempts had barely left any marks, but some turned out quite interesting, with clear marks. The experiments in which you attached carbon paper to some of the cutouts that I prepared worked quite well.

ABK:

CDPS:

Wasn’t there one that came the day after we finished putting everything up as well?

Maybe, because I think there were so many envelopes and some of them got lost on the way.

ABK:

I kind of love the fact that I sent them all off together, and then they went off on their own little jigs. I was kind of expecting some of them to just not turn up, because it's a bit of a suspicious package with all the pins that were in there. And then I was also worried that they'd all just arrive having not worked at all. But at the end of the day it really didn't matter, and it's nice that some of the ones did actually get used in the show.

TJ:

AB:

I also love the idea of these pieces being a real study into the combined British Portuguese mail services: light touch but inconsistent – good to know!

TJ:

You know, the only thing that Katie told me about was the envelopes; apparently Aline's dad said I have really nice handwriting.

[Everyone laughs]

KS:

I'm sorry!

ABK:

My dad was obsessed with your handwriting.

Germinating

So I hadn't been to a lot of the earlier meetings as I'd been in a massive art slump, and I was determined not to take on another project or be part of this, but at the same time I had been learning about weeds on my horticultural course. My tutor had mentioned how bracken is one of the only plants that grows where there has been a fire because it can return the burnt off phosphorus to the soil, so I thought that maybe I should do a bit more research into the reforesting that's going on in relation to the Portuguese forest fires of 2017 that claimed most of the Pinhal de Leiria. I then came across a scientific article which described the process of recovering from ecological disaster as ‘disentangling’, which was particularly interesting to me.

SE:

Seeing other people's work going up onto the piece, I wanted to make something that was smaller and perhaps more like embellishment. I was researching forest health indicators such as lichen and mosses whilst also growing wheatgrass roots, and thinking about making some pieces of embroidery that resembled these forms. I also wanted to link the idea of these interconnected species helping each other to survive through networks of roots under the surface to our own collaborative practice with Melt Club.

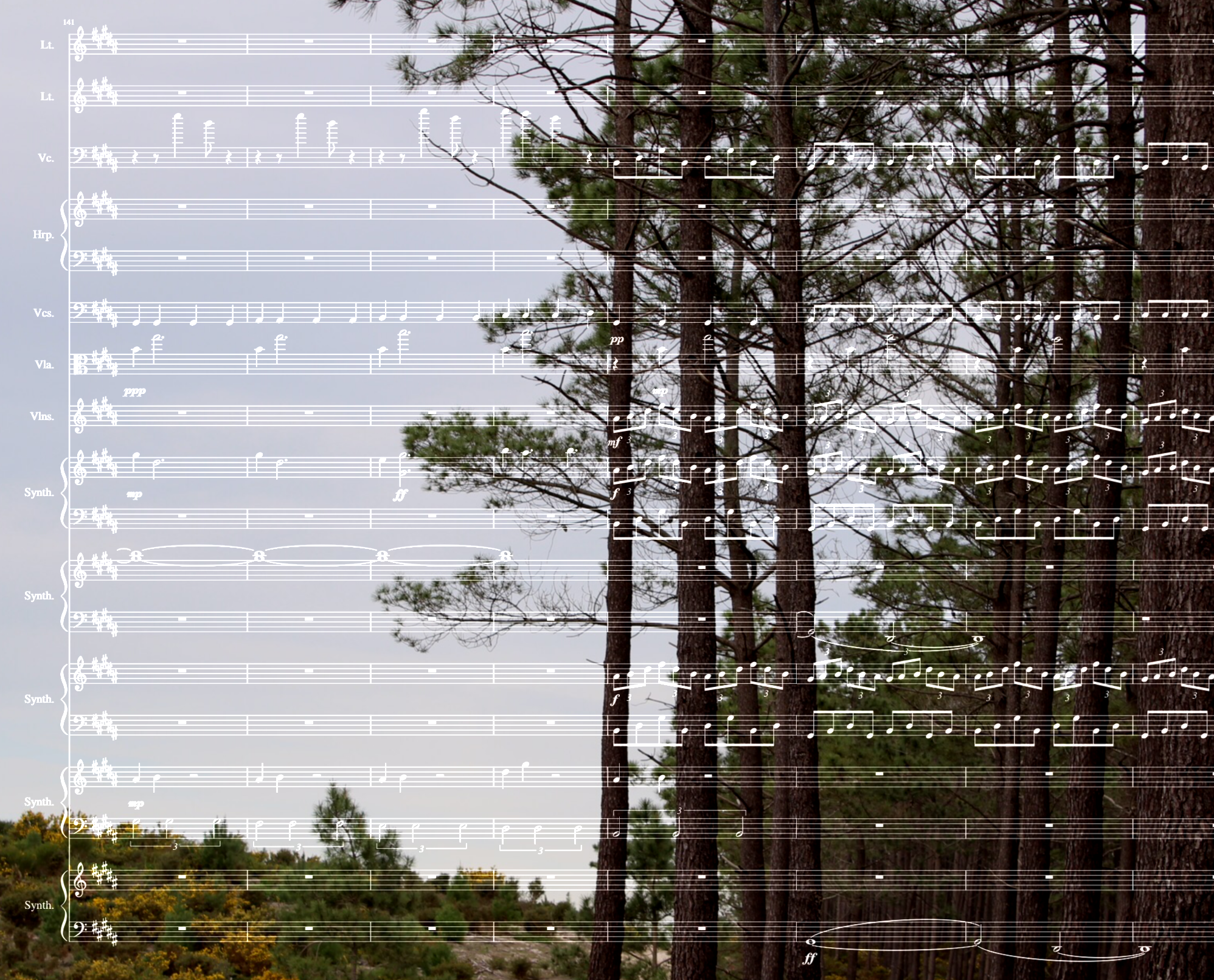

And then of course, the research about rewilding inspired the music.

AB:

And that music piece became very important to the show once it was made.

ABK:

Which is interesting because it came about quite late in the creation of the show.

I can’t remember… Did you make it knowing that there would be a dance response?

AB:

Yes. The museum asked us to select a piece of music since it had been decided that a group from a local dance school would perform at the opening of our show in the exhibition space. Initially I offered to help pick a piece of music to use, and I did a lot of research into different music that might be relevant, but in the end I thought it would be nice to have a more personal response. So I figured: why not give it a go?

I wanted to make something that was actually about the forest and the people. The music was supposed to be a kind of story of the town’s history of overcoming hardship, specifically ecological issues, and its ability to bounce back and thrive.

SE:

The music starts with a section which mimics the popping of embers and a fire beginning to catch, which turns into a larger blaze that keeps building. I was especially interested in the idea of making music about the fire because I knew the dancers were going to be using fabric, so I thought that it might end up with this dramatic flame-like effect. The middle section of the music, where it goes quiet, is representative of the ashes and then from this a germination, where it switches to a major key and shows the town coming out the other side. I wanted to use repetitive phrases throughout the piece to point to similar difficulties having happened before in the area, and while it may seem difficult now, that rewilding can be such a positive example of people making the most of a bad situation and coming together.

It was so special being given so many different opportunities to take more on. Whilst it was extremely stressful, I was glad that it wasn't just an exhibition. Maybe it was because we were just this random bunch of people who had flown in and brought all this stuff we’d made, being at the opening later on felt almost like a performance.

At the opening, João Correia, the son of the museum's namesake, described the installation as a backdrop to the choreography, which functioned as a set for the dancers. It was really cool how it all worked together as a performance.

KS:

We really had no idea what was actually going to happen on the day. The piece of music was created and sent off, and we also prepared pieces of fabric in the dimensions requested by the choreographer to be used as props, but we didn’t know them and had close to no information about what this performance would look like until we watched with the rest of the public at the opening.

ABK:

SE:

I think it was kind of nice having to trust other people, these people who we had never met and knew absolutely nothing about.

And the dance was amazing. It was so good.

KS:

It echoed the dynamic we had amongst ourselves, right? I mean, to work in the way we did, we had to have trust in each other as well.

ABK:

Hollowing

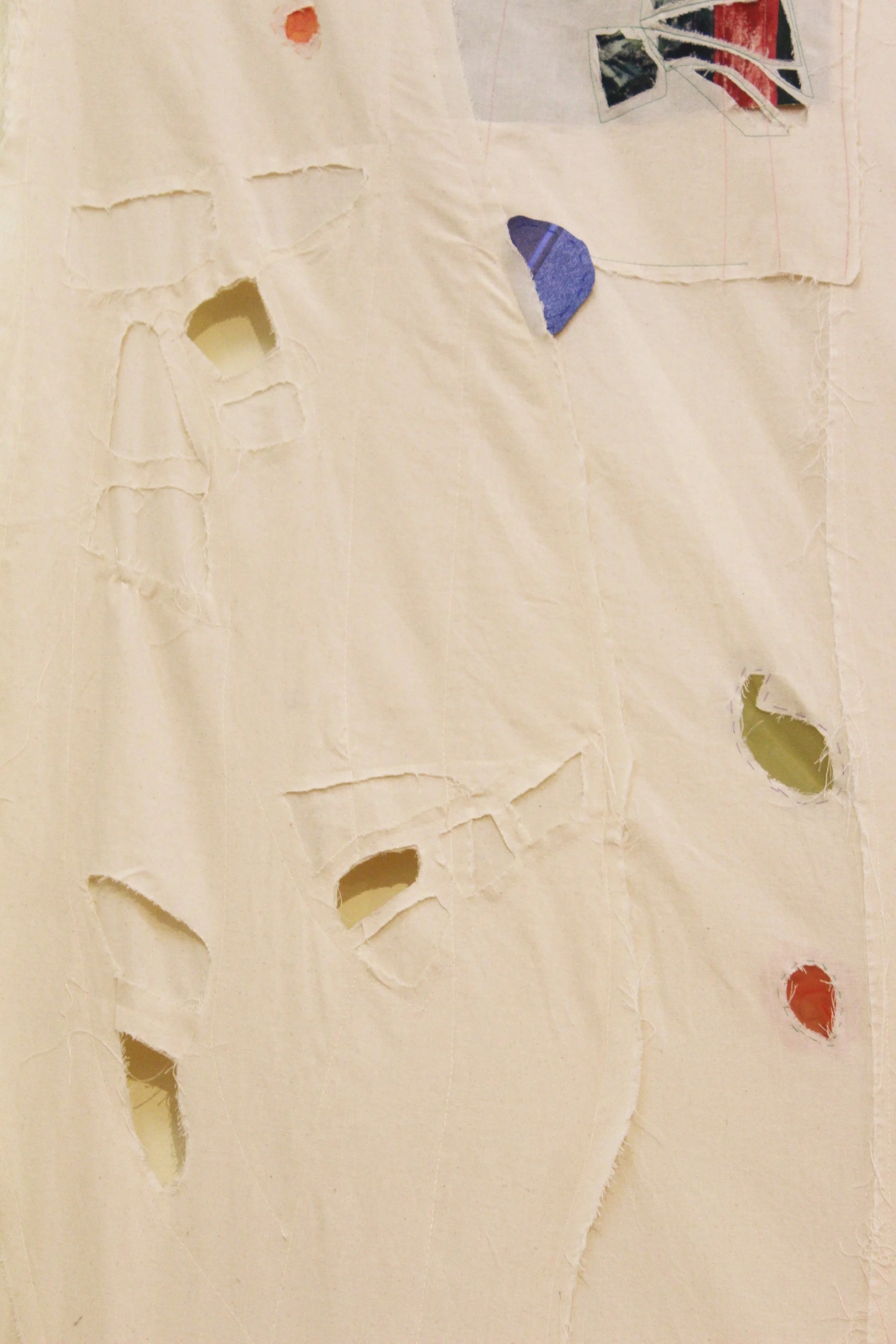

It was at this point, when everyone started bringing in their individual pieces and ideas that I started making little cut outs, using maps of the forest and the city for reference. I have an ongoing interest in separating elements of an image into fragments, and removing aspects of the composition. I thought it would be interesting to do that with different views of the city from a map, since that was a way of accessing the place from a distance, and so I found myself taking shapes from the map and then removing them from their original context.

These little pieces were then put into our larger collage, which in some ways works as a map in itself, of our entry point to this town. In this process of putting together a large composition, we thought similar cutouts could be a useful technique to tone certain areas down and insert motifs across the entire piece. With this, a specific visual language of cutting, overlaying and obscuring was introduced across the piece.

ABK:

On their own those pieces were beautiful, but then I think the repetition of holes all throughout everyone's work felt somehow like the final stamp, like the maker's mark or something, bringing together a selection of things that weren’t very cohesive.

AB:

There was one evening that really stood out to me as a decisive moment in that process. It was me, Christina, and Seb in one of the last meetings before the show. It was late and we were just staring at the whole piece. At this stage it was supposed to be almost done, but still we had this underlying feeling of “no, this doesn't look right. What can we do?”

It was only us three, so we felt weird about just going in and cutting things, it felt like a big decision to make - but we only had one week to go like we just needed to make these decisions. So we each got a pair of scissors and just started cutting holes everywhere! I think that was when you were both saying you wanted to cut the whole thing into strips or something?

ABK:

I feel like that was mostly me! The night before that meeting, at around maybe midnight, I remember Sebastian and I sitting and staring at the thing, sort of fantasising about just cutting it up into pieces. I think it had been a long day.

We then pitched it to Aline when you came around the next day and you brought us back down to earth.

CDPS:

Yeah, but there was definitely something about it that wasn't working though.

ABK:

I suppose at that stage it felt very much like a flat image, and I wanted it to have a bit more materiality.

I feel like we came up with an unspoken rule: if there's a minimum of three people and we can agree on it, we just do it. With just two people we might still be deluding ourselves, but with three, it felt like we could more confidently commit to a decision on behalf of the group.

CDPS:

ABK:

And it worked! We started by making these nice, tiny little holes, very carefully, but soon they started getting bigger and in no time we were really going for it.

You know, it was so interesting for me when I arrived one day,and I hadn't seen it for like four days or something, I came in and it was you, Aline, standing on a chair, cutting these massive holes! I was struck by the confidence with which you were doing it.

TJ:

Throughout the whole thing, because of how people were coming in and out, it was important that we developed a way of making decisions without everyone being there. We wanted to keep people on board with what was happening, but that became sort of impossible; there were so many of us! And we were meeting so often that obviously not everyone could be there consistently.

ABK:

That probably made it happen. We’ve described this whole l thing as this overarching exercise in letting go and not being too precious with anything. I think artists very rarely let go, and very rarely stop being precious about their work on that kind of scale, so I think all of us making our bits, parting with them and then agreeing “whatever is going to make this work, make it happen! Cut holes in it, chop it up, sew into it, I don't care”, I think that’s what allowed it to all come together.

MP:

Sewn In

For the people who didn't have a textile practice before this show, how was it for you to adapt to the medium and do the hand sewing and everything else?

CDPS:

I had a very textural practice before, but I’d never really made anything using actual textiles, and at first it was great! I was so into trying to learn something new and it's so tactile, which means that it often feels very intuitive to just get your fingers all over it, you know? I was a huge fan.

AB:

But that quickly turned into a lot of frustration. I have a set of skills in life, as we all do, and I have a set of inadequacies as well, apparently. One of those is absolutely with textiles. I don't know if it's the size of my stupid fingers or something, but something about the intricacy just does not come naturally to me. Of course we were very DIY about the whole thing, desenrascanço and all that, but there was a certain level of quality we needed to maintain that I was not able to provide.

I really did try, but I found myself dissociating from that side of the work quite quickly. I think the exact moment was when – and I didn't take this personally at all – I saw Seb take a piece of stitching that I'd done down and redo the entire thing.

Sorry… [awkward laugh]

SE:

No, don't be. It's better now.

AB:

CDPS:

It was a collective decision. [laughs]

Yeah, that makes me feel so much better, thanks for that. [laughs]

Maybe in a hundred years I could get good at sewing, but we didn't have a hundred years, we had about two weeks, right? So that was my personal experience of textile.

AB:

Interestingly, speaking specifically to sewing by hand, I had quite a different experience to you, Alex. It was something that I'd kind of written off. I've a short attention span and that's the sort of thing that I never thought that I would enjoy. In the end I actually found it so therapeutic, especially after a day of work and with everyone sitting there together. After all the big decisions had been made, we could all just sit there doing some sewing and have a nice conversation or listen to a podcast.

I really enjoyed it. And, you know, the quality of my sewing probably wasn't incredible, but I think I formed a new relationship with making and crafting in that way.

TJ:

It was really sweet at points, wasn't it? When we were all just sitting on the floor under this massive piece of cloth, all concentrated on the sewing – I stitched into my trousers at one point which was great. [laughs]

ABK:

Marinha Grande

It was quite strange when we arrived in Marinha Grande for the opening. It felt a bit like I was bringing people home – my parents live in the country and I speak the language – but really that just wasn't the case; I’ve never actually lived there. So it was a strange situation for me, and although I had the most familiarity, in most ways we were all entering a space that we had very little to do with.

ABK:

Yeah, it was surreal arriving at the actual place, it was more industrial than I was expecting. I was excited because on the way we passed by places that I’d seen before when I used to visit the region with my family, but when we were actually coming into Marinha Grande it was very unfamiliar. There are these huge warehouses where they manufacture plastic – I think specifically plastic moulds – and they’re these massive, very flat buildings.

KS:

Then once we came through the town and arrived, the museum itself is this bright, colourful building. The day we arrived was pretty bleak, as you’d expect from December, but there it was. It felt so big. We'd seen it before in Aline’s photos of the building, but actually being there was very special.

Throughout the entire project I was trying to portray the town and the museum as accurately as I could to you guys, trying to be realistic about the place as I was the only one who’d visited it before, but it’s tricky to fully convey a place, even with photos.

ABK:

Weirdly, I found it kind of nostalgic. There was something so familiar about it even though it was not what I was necessarily expecting. I enjoyed the drive there, seeing the landscape was amazing; I had no idea that it was such a beautiful area, especially on the way back to the airport when it was all foggy. Then the town, its houses, the tiles and all the colours, it was just really quiet, and surrounded by, as Katie said, these big bleak buildings.

SE:

AB:

How did that make you feel about the work that we were bringing to this? I know in our context the work sits in this very DIY place. What does it mean for people to come face to face with this thing that we’ve had in Christina’s kitchen for the last few months and receive that with anticipation or even excitement?

I mean, it still felt very DIY. We were on the floor ironing things the day before. But I guess there's something that happens when you walk in on the opening day and there aren’t any ladders or extra bits around; it feels fully formed, like a real piece of artwork.

When we were explaining our process of continuously collaging different pieces at the opening, someone asked us about how we knew when it was done, and honestly? I’m not sure that point ever really happened for us. It was over when the time was up. It was done because it had to be done.

CDPS:

It seems like that speaks to Desenrascanço as a concept, the available means being the time in which we had to make the work.

AB:

I think Catia really enjoyed it because she uses that word to describe her hands-on approach at the museum, so it was all very in line with our approach. Any time we had a problem with the installation, or if we lacked resources, we were always very ready to find a workaround. It worked quite well in the end.

I had been to the museum before so I knew roughly how it worked, but still I was surprised to experience just how DIY it was. I feel like the meaning of the word really kicked in when we were mixing acrylic paint to match the colour of the walls to cover up how it was peeling. It wasn’t perfect, but it worked well enough.

ABK:

I enjoy that because it feels like this ongoing DIY nature which became so important to the works’ creation and subsequent installation is another way in which this was a site responsive piece of work, another way that the site from a very early point was embedded into the DNA of this exhibition.

AB:

In relation to that idea of the site-specificity, it’s also worth mentioning that Aline had taken measurements of the space, so the work was made specifically for that room – we hadn’t just gone there with pieces to hang up on a wall. I do remember liking it in Christina's kitchen, but it was a completely new experience when it came to where it was meant to be.

KS:

SE:

It was like we were only then seeing it in the correct context ourselves. We all had these moments of panic thinking, “Is this bad? Does this suck?”, but when it finally got there we were immediately reassured; it didn’t suck. We just hadn’t been looking at it right.

Workshops

While we were making the show, we came up with a very specific way of making work. When we translated that into the workshops, it suddenly felt like our approach actually made sense as a methodology. We participated in those workshops as well, so we were able to experience that at the same time as the people who were there, and ultimately it was a really enlightening experience for us.

ABK:

AB:

How did those workshops compare to the time we spent making work together in the kitchen? Were there parallels between those experiences?

I think during the workshops we felt more comfortable making shit work than we did at home. It was almost like we were trying to show other people that it was okay to do that, to show how comfortable we were at just drawing whatever thing is in front of us without the pressure of making something “good”. In theory that’s something we're always very much for, but, I think it’s fair to say that we do often struggle to get past that pressure to make something good. In that environment, however, it felt important that we were very free with it, and so it was easy.

ABK:

Perhaps we were less precious because when we started making our big piece, we were very careful that everything we did had to be perfect, but by the end we were very liberally cutting holes in everything. Once we were doing the workshops, we’d already taken the time to become very comfortable making complete crap, and I think that made it fun. I, personally, had a fantastic time seeing other people making and being happy to work on top of other people's work. I distinctly remember seeing one of the kids making work on top of a really nice drawing that someone else had made, and it was very freeing to see someone with the confidence to do that and not worry about it at all. It was so playful.

SE:

What was nice in those sessions was how you wouldn’t expect it, but the work would improve every single time. We had some of the drawings go through maybe four or five iterations of being swapped, cut up and evolving, and they just got better and better. It helped that the participants were so open to it.

KS:

It was also interesting when we had workshops that included multiple age groups. For example, in the children-only sessions we had the kids make “exquisite corpse”’ drawings, where they took it in turns to do the head, body and legs. They were all very happy to get on with that – they found that really funny – but when we later suggested swapping with someone else to work on top of their drawings, they all had a meltdown. However, when those same kids were in a class with the adults later on, they suddenly were completely open to it; they saw the adults drawing and it became fair enough that someone else could draw on top of theirs. I suppose with the other kids they felt that they could act out if they didn’t like what they were doing.

Yes, it was much more difficult running those child-only workshops. They all arrived at different times and they each had very strong feelings about what they did or didn’t want to do, so it took a lot of convincing to get them to take part. By the last half-hour they had completely lost interest in anything we were doing and were just running about outside.

ABK:

I get it. That was me at like 10pm after hours of making work at Christina's house, needing to run to Waitrose for a treat.

AB:

“Why”

When I spoke to Catia the other day, I asked her how it's been going with the show and she said: ‘Yeah, I don't know if people understand it’. I tried to say that there's not really such a thing as “understanding it” but I didn’t know how to explain it. I think there was a want for an explanation that maybe we're not able to give. She’s never said to us that it’s going great, or that everyone's loving it, but she always makes a strong point of saying that their visitors aren’t used to “looking at art”. I suppose the piece might look exciting to some people, but like a collection of meaningless scraps to others. But, yeah, when it came to trying to articulate what the show is “about” and what it “means”, it felt like we couldn't get away from those questions in this project because people would ask us directly, forcing us to collectively come up with an answer; I don’t think we reached a point where it felt like we had a satisfactory one.

ABK:

AB:

You're always going to have that same interaction, I guess, that's the sort of thing we’ve always heard from people who might be more cynical about art. We have to accept those reactions.

Thinking about the piece totally out of context, it is weird to imagine walking into that museum and being confronted by this massive scrappy collage. I don’t know how I would approach it if I hadn't seen it before. I do think it's a work that you need a bit of time with, and maybe that's asking too much, but I think you enter it by finding something in the collage that you like – a little moment – and then you go outwards from there.

CDPS:

Maybe this feeling is a reflection of how we entered this. I have a feeling that if we had all visited Marinha Grande and the museum together, and then each responded independently, we wouldn't have had this early feeling that we need to justify it with some sort of purpose or intention. Whereas in reality, we didn’t have that option. How do you respond to something that you haven't really experienced? That's a weird thing to do in itself. Because of that, I think early in the process there was this impulsion to frame what we were doing with some sort of wider purpose; I don't think we ever came to one. It was trying to find meaning where there is none.

AB:

I mean, in the end, that’s what's most interesting about the work, right? The process.

ABK:

We can be proud of this show for what it is, and I totally agree with you, Aline, when you say that the process is an interesting and important thing to document.

AB:

But I don't think I want the work that I make to only be interesting on a meta level – because that's what it sort of becomes! I want the content to be interesting and worth engaging with in its own right. I suppose the process can be the content, sure, but these experiences are specifically interesting for us as artists to look at because we never really get away from elaborating our own processes. I guess what excites me more is to imagine this process becoming a bit more concise. That being said, I do still think our show is interesting in what it does rather than “how it does…”, but maybe it could be elaborated further in the future? Does that make sense?

Though I was surprised by how it looked in the end. There is a lot to it, and there are a lot of small details that act as entrances to the work.

But this is a wider issue, right? I have the same problem when people ask me about my personal practice, not having an answer to what my paintings are “about”. So anyway, I don't know if it's a very realistic aim to say that next time we make something, we’ll have all those answers.

ABK:

This has been really interesting for me throughout working on this project. I've thought about it a lot coming from a design perspective, and working with you all has been so eye opening for me. I’ve learnt to let go of needing to find an answer, if that makes sense.

Whenever I was working on a project for uni I always had a brief, a problem to solve, and once you figured that out, that was your answer and the project was done. I think I felt quite uncomfortable about the fact that I couldn't work out what this piece of work was going to do. You guys got your resolve when you saw it in the space and it all made sense – I think it would have helped me to have seen it too.

TJ:

I think in the wider context of art everyone's asking those questions. When you listen to artists speaking about their work, some don't give reasons for doing what they do and instead it's a continual process of figuring out why am I fascinated by this? Why am I doing what I am doing? In our piece there are all of these aesthetic choices in how we selected colours and matched things together that don’t necessarily work to a larger logic. At uni I looked into artists that use intuition and coincidence in their work and now, listening to this conversation, I'm wondering: is that not everyone? I don't know if that’s how everyone works, but I think it is how a lot of us work, through those little similarities and coincidences.

KS:

ABK:

In a very simple way of looking at it, the process is the why. It’s the reason we stopped doing what we were doing in our lives and met up to work on this thing. Then it became the thing that people will take time to look at in a museum. That's what it is, right?

And we all like doing it! That's why I'm involved in this project, because I want to be around people that are inspiring and be making, doing and coming up with ideas together. That's also our “why”, I guess.

TJ:

Yeah. I think I'm okay if the “why” is the process, especially when working with such a tactile medium, I find that the act of making exists in the final piece so much more than in other mediums; you get a lot of the process just from looking at it.

CDPS:

I agree with you, but I really resonate with Tooey’s comments about this feeling of discomfort with that as well. Maybe I worry that there's something that feels – and I don't think this is correct – but something that feels inherently narcissistic about wanting or expecting other people to be interested in your process… I don't think that's true. I suppose other people’s processes are interesting as an artist or a maker because it can shed light on your own practice when you see it.

AB:

That’s where the workshops come in as well, because then we're inviting people to be part of that process.

ABK:

It becomes something more than just putting out a work for people to look at.

CDPS:

AB:

And there the process being enterable can be joyful and light, as the experience of mark-making is supposed to be.

I also think you probably have to be a little bit narcissistic to be an artist. You're putting something out into the world and demanding that people look at it. Even me, as someone who is quite self-conscious about my work and putting it out there, I still do want people to see it, you know?

CDPS:

I don't see how the process is any more self-important than anything else that we might want someone to look at in a piece of art.

ABK:

I suppose when the focus is on process, the subject becomes the artist rather than anything external, but to be honest maybe that’s always the case. Yeah, no, I do agree. I think I'm just trying to articulate an irrational discomfort I have with that – I don't think I'm right in that feeling. I do think it's valid. Also, talking about people who might be “outside” of art, I think anyone can be interested in those things, and it would be patronising to assume that they wouldn't.

AB:

What’s Next?

I think it's going to be really interesting to see where it goes after this show, and what happens next for Melt Club. I don't know how much everyone has really thought about that, but I think I definitely feel like I'm just now getting the sense of what it is like to make work in this way.

TJ:

Since this project started taking shape, we’ve started making a lot of comments about how we should approach it “next time”. I would say that there’s very much this sense that we’ve only begun to figure out how this process works, and that this was a very turbulent first go at it. Now that we have a process, it feels as though it would be really valuable to redo it somewhere else and with a clearer idea of how to approach it. There was definitely a specific point where we all-of-a-sudden became comfortable working in this way, so I think we absolutely should repeat this in a different context and see what happens.

ABK:

It would be really interesting to repeat the same methodology in a different place. What would that look like? Would we get a similar result?

AB:

I'd be interested to see what kind of form it took if we didn't have fabric as a base, because that was obviously very specific to the place and the fact that we were transporting it. Would it end up being fabric anyway? I suppose that serves collage well.

CDPS:

When we were coming up with the first iterations of what this could look like, we really didn't know what we were doing. We did this research and pooled it as soon as we found anything that might be something to latch onto, and that definitely was reflective of our uncertainty in how to even begin with this. For me, the “eureka moment” was learning about the Pinhal De Leiria as this entity which is so tethered to the Marinha Grande’s history and holding all of these genuinely emotive stories. However, I am aware that this approach also aligns very much with my own practice, and instead it would be nice if we could silo our practices to develop independently and intuitively, and then manifest a body of work together through workshops without prior conversation.

AB:

ABK:

I think a small version of this is what we did in the workshops. We didn't say anything other than to ‘go around the museum and draw whatever you want; it could be anything. It could be the view from the windows, the architecture, the artwork, anything’, and everyone just ran off and found something. I feel like it led to a wider range of ways of looking at a place.

Being in the space that we were responding to made a difference as well, and that is also something I'd really love to try: this same process with a space that we could visit more easily.

AB:

I suppose it's exciting for me to think about this as a shared collaborative practice, and one that is still in process. We found our direction with the work very late in the process, and we are still now coming to our own understandings of it – I know I'm still in the process of doing that. I do think that if we repeated this process, there would also be ways of clarifying the work and perhaps we could make it more enterable by defining the work’s parameters and intention for ourselves, as well as for whoever was experiencing it. Maybe that would take away some of the curiosity of the work, I don’t know.

I personally love the idea of considering the process as a holistic and artistic autoethnography of a place, where our practices respond to a place in their own way, and we layer that, and that's the framework. It would of course be approached sensitively, but there would be no resolution – we’re not qualified for that – it would just be a shared rumination on a place.

Right. I mean this was a wonderful opportunity, but we were limited by the fact that we couldn't see the space. There's very little to go off from photos, and so the research had to be very Wikipedia based. Though it pains me to admit it, there’s only so much that Wikipeadia can give you, whereas if we were to enter a space, wander off and let ourselves be drawn intuitively, that would perhaps feel like a more unfiltered version of the same process.

We should do it. Let's choose a spot.

ABK:

Desenrascanço, however, was the centre of this exhibition. We couldn't do that again, you know? That was this one. But I think that the wider approach that we developed through this exhibition could be applied and exist outside of that.

AB:

Yeah, when we say we have a process ready, it's not like we can just recycle it and just do it all over again; we have a better understanding of how to work together and in this sort of way. Of course we’d come up with a whole new concept for a future project, but it will be exciting to start a bit further along.

ABK: